12 months focusing on the wrong solution. One week to turn it all around with a design sprint.

Introduction

When LRN, a company based in Montreal, came knocking on our door (by which I mean they gave us a call) to discuss an adaptive learning platform, I was excited. Both of my kids go to public school, a fact that gives me countless headaches. This, of course, will surprise no one: the American education system is riddled with problems. Now, adaptive learning has been touted as a way to address key issues like student-teacher ratios and low graduation rates. It uses automated teaching to “adapt” the educational content (and to assess the mastery of that content) to each student’s needs and abilities.

As the guy who runs New Haircut, a software design and development firm that uses GV design sprints to take on big challenges, I immediately knew LRN was a great candidate for such a sprint. First and foremost, because their end goal was ambitious: LRN wanted to develop a platform that would one day potentially fix the public education woes. Second of all, because the founders were stuck. They went through all the trials and tribulations of starting a company and were trying to avoid another mis-step.

The Sprint

Day 1: Understanding the Issue

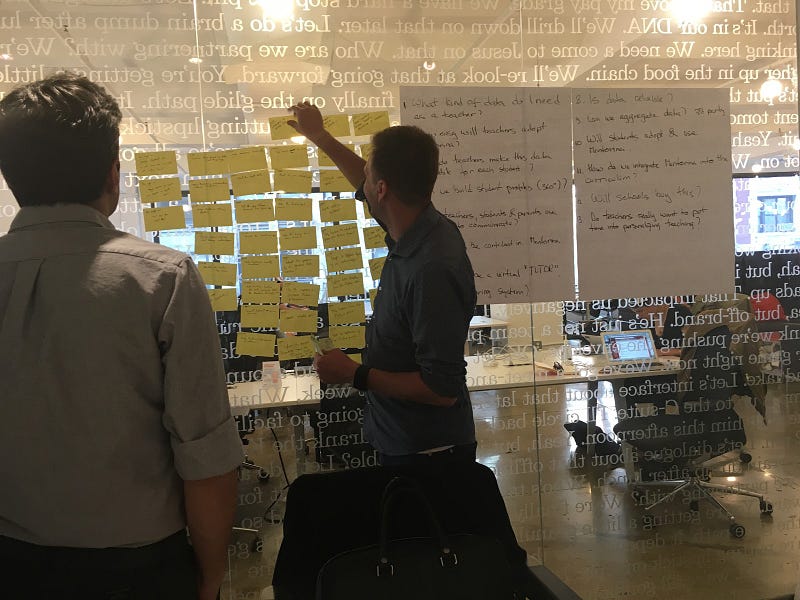

On the first day, our collaborative team of six started mapping the challenge. Creating a platform that serves multiple groups is always tricky. Everyone involved–which in our case meant teachers, students, parents, and school districts–has different needs and pain points. Yet, the rules of the sprint state that you have to pick a manageable piece of the problem that can be solved in one week. As excited as we all were to work on this, we had to remain focused and choose one customer and one problem.

We knew this much: parents enroll their kids in private schools because teachers, who have smaller-size classes, can dedicate more attention to each kid. “Let`s focus on teachers” said Malcolm, one of the LRN founders who has been studying education for the past two decades. Now, reducing the size of a class was not something an adaptive platform could do. But freeing up class time was possible. If the LRN platform could enable teachers to build personalized lessons in a short amount of time, they would spend less time transmitting knowledge and more time guiding students through that knowledge.

One teacher actually told us “I feel like I spend so much more time doing paperwork and grading than I do developing lessons… by the time I got through giving them all feedback, it’s too late for them to make meaningful changes.”

Our goal for the sprint was to figure out how a technology platform could help teachers effectively build personalized lessons.

Day 2: Sketching possible solutions

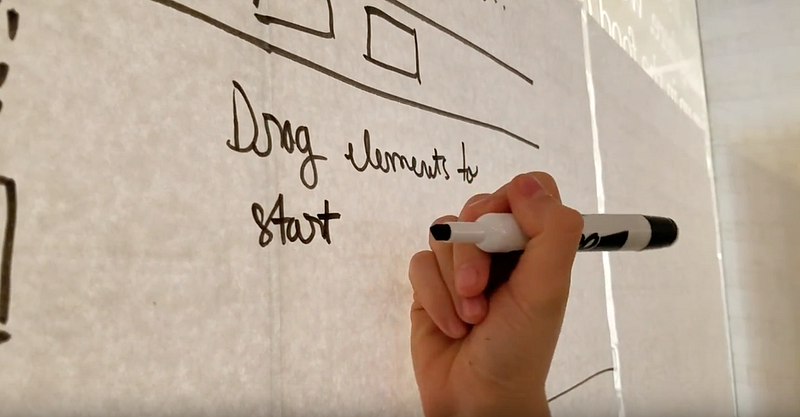

Day two was all about visualizing solutions. Everyone in the team sketched (even those reluctant to do so). We made significant progress toward finding our winning solution. After speaking to the experts a day earlier, we learned that in order to build personalized lessons, teachers must have a clear understanding of where each student stood in relation to his/her individual needs, capacities, and interests, as well as within his/her group of peers. This led us to believe that individualized reports about each student’s performance might make it easier for teachers to tailor educational content. Most solutions sketched on Tuesday included some sort of reporting.

Day 3: Deciding which solution to prototype

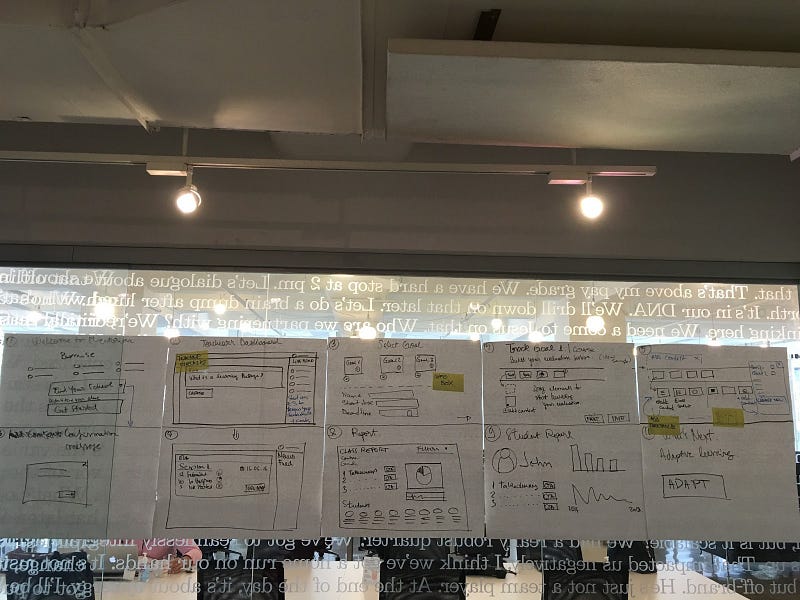

All the sketches were silently critiqued on Wednesday. The official deciders, which have super special voting powers, eventually picked a solution they considered most likely to help the sprint`s mission.

To be fair, it was not (and it never is) just one solution. It’s more like scenes from several sketches linked together. In our case, we chose one that showed how the LRN platform could aggregate the student performance data into individual and class reports.

The one pitfall of this solution was getting the specific information about student learning goals and metrics in such a short amount of time. We had an idea.

Day 4: Prototyping

On Thursday morning we put the prototyping on hold for a few hours to hold additional expert interviews. Our thinking was that this second (and more targeted) foray into the minds of the experts could shed some light on the goals and metrics section. It was a calculated-but-risky move, as in you should not try it if this is your first sprint.

When the interviews were done, we began working on the prototype. We used Keynote and InVision to build it. The prototype was rather complex for a design sprint and building it was a challenge given the short amount of time (repeat after me “15 functional screens”). It had five sections: Welcome, Dashboard, Goal Library, Learning Sessions and Reports.

Day 5: Testing our prototype with real users

Given our attempt to screen additional experts on Thursday, we were right up against our deadline to complete the prototype in time for customer testing. In fact, we finalized it minutes before the first tester arrived.

A few patterns emerged by the end of the day. Teachers found the personalized learning sessions module to be confusing and potentially time-consuming — this was expected since we missed key data in the goals and metrics section. However, they were extremely receptive to the student and class reports. They were excited that such reports would provide a snapshot of each student and allow teachers to take specific actions while the lessons were still underway — which is to say while there was still time to help, therefore avoiding low graduation rates.

We were able to test our hypothesis that reports were key in helping teachers build personalized lessons. We were not able to vet the goals or measure and validate which students skills are important. But that would certainly be open game for an upcoming sprint.

Takeaways

So do we know exactly what a successfully adopted adaptive platform will look like? The answer is not yet. But the sprint helped us get steps closer. Sure, there are still loose ends to tie: at least one additional sprint will be required to validate the goals and metrics section and confirm our final MVP approach. But within one intense and hyper-focused week, we had LRN back on track, identified the missing pieces and were ready to define their 6-month product roadmap.

Before the sprint, the LRN founders were not so sure where to go next. They lost time and money building a learning management system, which wasn’t truly solving a market need or highlighting their strategic point of view. Their stress levels were through-the-roof. This caused spirited debates and inaction. But these things are normal within ambitious companies: the potential of (yet-another) failure is always lurking. During the sprint, they had to let go of their differences and unrealistic goals, prototype a viable solution and test it with users.

The design partners at GV warn that sprints “only work if you begin with the right foundation.” While we at New Haircut adhere to this gospel, the LRN sprint showed us that even when you start with a somewhat shaky foundation, a sprint is incredibly valuable and can right just about any sinking ship.