Problem Framing v2: Part 2 of 4

In Part 1 of this series, we covered Step 1 of 5 — Problem Discovery — of our Problem Framing process.

In Part 2, we’ll cover Step 2: Business Context.

Head’s up! We just launched our brand new Problem Framing Toolkit — a comprehensive kit containing all of our training and do-it-yourself tools&templates to equip you to facilitate your own problem framing workshop!

Establishing business context is important for creating the connection between the problem and the larger strategy goals of your company. Otherwise, if you’re working on a problem your stakeholders, leadership team, board, etc are not aligned with, you’re starting off on the wrong foot.

Before digging into business context, we need to get familiar with the customers of our products and services.

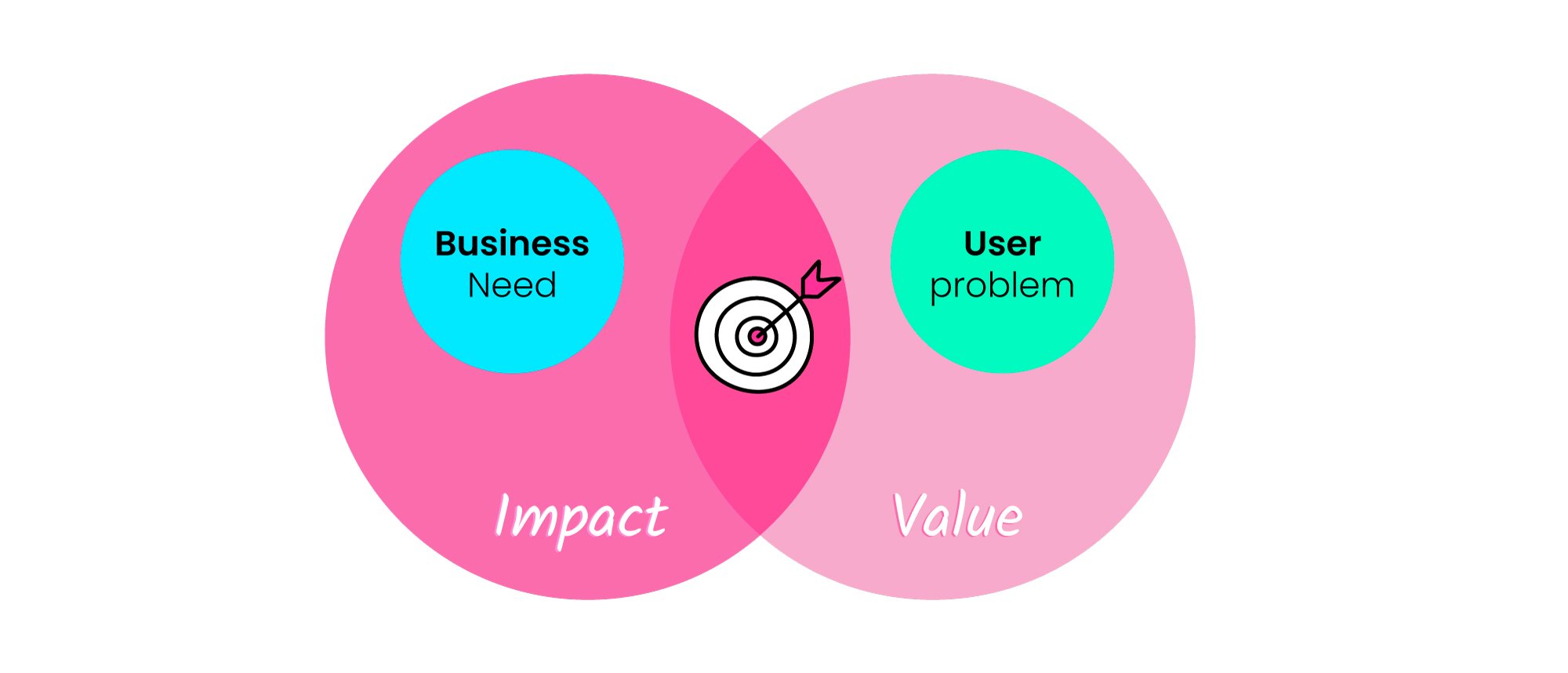

Business + User

There are 2 customers we need to consider during any sort of product discovery work (research, framing, sprints, etc): your business / company and your user.

I use the word customer because the business needs to buy into the impact the product/service will have and the user needs to buy into the value it will bring them.

Products and services that consider both customers, tend to land within a sweet spot. However, most organizations that stumble with launch after launch, do so because they’re think only about the needs of the business.

So in terms of chronology — problem framing begins by getting familiar with the business needs. Next, you focus on the user. Then, you explore the space in between, where there are user problems that the business is excited and capable of solving.

Let’s now dig into the relationship your company has with the problem.

Step 2: Business Context

[Time allocated: 60 mins]

Thanks to the user-centered spirit and mindset of disciplines like UX, CX, design thinking, design sprints, etc the users of our products & services are receiving more and more attention. However, there first needs to be a reason the company would be willing to spend any resources working on a particular problem.

In startups, the founders may have experienced the problem first-hand and are now working to solve it as their initial, primary business offering. However in larger companies, the problems you work on often need to map back to strategic goals — otherwise you’ll face an uphill battle acquiring the executive sponsorship needed to move forward.

There are 2 components to establishing business context by building upon the team’s current view of the problem:

Problem debrief — adding to what you already know about the problem in relationship to the company

Impact —building group awareness about why the problem is worth solving, what could go wrong along the way, and how you’ll overcome

Part 1 of Business Context: Problem debrief

This is the team’s chance to work collaboratively to share what they know about the problem space you’re attacking. Below are several techniques you can experiment with to surface this info, primarily depending on how new the problem is to your team & company.

SWOT

In reality, the majority of problems teams tackle are well-understood — ones the company has been circling around for months, years, or even decades. In such cases, your team will have a lot of insights that can be collected, sorted, and analyzed. A great tool for doing so is a SWOT.

By looking at the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats your company has in relation to the problem, your team will develop a clear, well-rounded — current vs. future and internal vs. external — picture of the relationship between the company and the problem.

Good for: When the team has at least some experience & data on its company’s position in the market, related to the problem.

Avoid when: Working on an entirely new problem.

Gilfoyle and Dinesh of HBO’s Silicon Valley use a SWOT to determine if Pied Piper should let Blaine die.

Maps

If you’re moving into new and/or complex scenarios, maps help to visually organize a high-level picture of what’s going on in the surrounding industry by identifying key influencers, players, trends, challenges, and markets.

2 somewhat similar maps to consider:

Industry Structure Maps

Context Maps

Business Model Canvas

Another popular tool for laying out the critical data points, triggers, and needs (e.g. customers, partners, channels) of a new problem space is a Business Model Canvas.

For both maps and a business model canvas:

Good for: Working on new problems and the team has some ideas about the surrounding business opportunity.

Avoid when: Working on legacy / core business problems — the team will feel like they’re wasting time with info everyone is already aware of.

Part 2 of Business Context: Impact

During Problem Discovery, enough people agreed that this problem is an important one to solve. Now, it’s time to understand why it’s important. To do so, the team will pose a series of questions and scenarios to think through individually, and then converge and discuss.

The entire team may not perfectly align afterward but it will expose those inconsistencies and provide the info you’ll need to decide if and how you can continue to work on this problem with this team.

1. Default Future

For processes like these, there will bealways be tire kickers and instigators who are too racked with worry and hesitation to take action. This is your chance to run with that theme and ask yourselves, “If nothing changed, what would the future look like?”; i.e. if your team did nothing about this problem, what would happen?

This is your chance to unload all of those fears this problem may or may not cause — think of it like group therapy. By doing so, it might just inspire to do something about it. Or not, which is another acceptable outcome at any point throughout framing.

2. Derail

While staying on the negative and pessimistic track, ask yourselves, “What could we each do to derail our outcomes?”

The Stakeholder might divert budget.

The Engineer might overstate the complexity of building.

The Head of Design might horde her designers for a project she’s more excited about.

The PM might claim that users don’t care about this topic.

The VP of Customer Success might lobby to focus on a different segment.

3. Why derail?

Keep going with the previous question to understand the meaning behind each person’s resistance. Ask, “Why would we derail the outcome?”

Because the Stakeholder is afraid that if this fails, his budget will be reduced next fiscal.

Because the Engineer knows 3 solutions that already exist to this problem.

Because the Head of Design thinks the idea is stupid.

Like therapy, right?

But this is important, especially for teams working in environments where trust is low and new individual ideas are rarely championed; i.e. many enterprise cultures.

But cheer up — the next 2 questions leverage these objections and obstacles to find success and rally the team forward.

4. Success elsewhere

You aren’t the first group of people working through similar obstacles and you won’t be the last. That means others have pushed through, even in the most bleak conditions. Ask yourselves, “Who else has been working on something similar or within a similar environment, yet managed to find success?”

5. Replicating success

With the list created from #4, ask yourselves, “How can we achieve the same success?” Quite simply, if they can do it, you can too.

Wrapping up Business Context

Hopefully your team used the past hour to build a deeper, team-wide understanding of the problem, as well as become aware of the impact the problem has on the company.

Later, when it comes time to pitch stakeholders for additional people and budget in order to build solutions, the points established here can be leveraged.

And with the company’s interests covered, you can now turn your attention to your user.

PART 3 NEXT: Building collective empathy for the users experiencing the problem.

Completely updated tools & process (as of 2020)